Guardian of Hawaii’s Sacred Sites & Indigenous Rights

When Lahe was brutally executed in 1999, some might hope she went straight to heaven. In light of her devotion to the study of Hawaii’s pōhaku, it might be more appropriate to wish her extraordinary spirit sticks around, breathing life into stone. Perhaps her energy abides, providing a strong foundation for all those who will come after her.

Laheʻenaʻe Rebecca Hart Gay (1959-1969) was a indigenous rights activist, photographer of Hawaiian sacred sites, and writer. Her paranormal work focused on documenting and preserving hallowed stones, believed by Hawaiian traditionalists to contain spirits. These guardians of lands and families are called pōhaku.

In the Hawaiian afterlife, there are a variety of options. Of course you can leap into the next world, but some ancestors, choose to stay. Perhaps Lahe still remains and continues to inspire.

Some spirits don’t wander, but instead serve an important purpose. In Hawaiian spirituality, supernatural protectors watch over family members or sacred places. Called ʻaumakua, these guardians typically take on the form of animals like owls or turtles. For example, Jason Mamoa’s ʻaumakua is the shark.

But ʻaumakua can even take more surprising forms including sacred stones. These are called pōhaku. Pōhaku can be imbued with spiritual power which may account for the paranormal activity that has surrounded many of the archipelago’s sacred stones throughout the ages.

Indigenous rights activist Laheʻenaʻe Rebecca Hart Gay was called Lahe by family and friends. According to them, Lahe did more to preserve pōhaku traditions than anyone else. This is her story.

This updated resource guide aims to put all relevant information about Laheʻenaʻe Rebecca Hart Gay’s contributions to fields of paranormal study in one place.

What did Lahe Gay do that was so influential?

- Lahe Gay documented the sacred stones of the Hawaiian Islands.

- Lahe Gay made Hawaiian spirituality more accessible.

- Lahe Gay devoted her life to the preservation of native wisdom.

1. Lahe Gay documented the sacred stones of the Hawaiian Islands.

Concerned that the spiritual foundation of Hawaiian spirituality was been eroded by looting and development, Laheʻenaʻe Gay embarked on a 7-year-quest to document all of Hawaii’s sacred stones. According to Lahe, these pōhaku called out to specific individuals seeking protectors.

Lahe claimed to be one such protector trained by Hawaiian elders from the age of 4. The dreams sent from the sacred stones began at age 8.

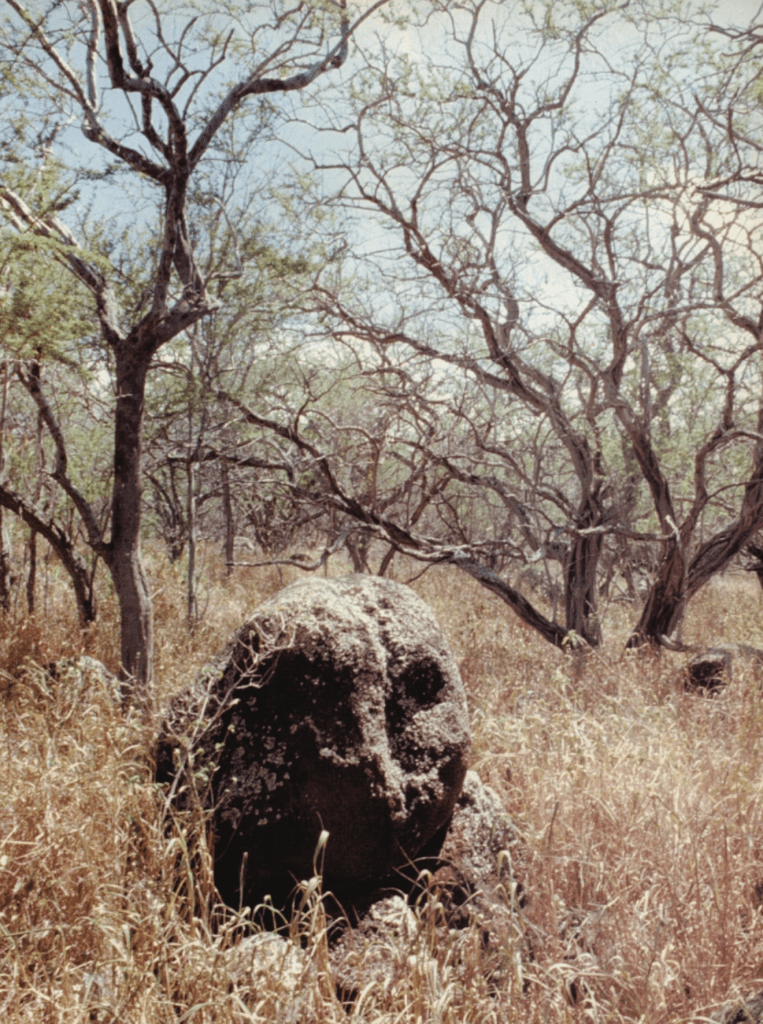

An adventurer known to rappel down 100-foot cliff, Lahe embarked on an ambitious project to locate, map, and photograph every known stone site within the Hawaiian Islands. The journey resulted in a photographic catalog of 2,400 diverse sacred stone sites, many of which were at risk of destruction due to modern development.

The Owl Stone of Molokai

One of the most thrilling moments of Lahe’s research was her rediscovery of the legendary Owl Stone of Molokai. Lost since the 1800s, the strange rock is called Pōhaku-o Pueo, and represents the owl ʻaumakua.

During her search, Lahe nestled on the ground in a sleeping bag was roused from slumber by the racket of dozens of owls roosting nearby. As the dawn broke they flew off in unison. Lahe sat up and found herself staring into two large grey eyes. Momentarily panicked, she attempted to quickly back away, but still stuck in her sleeping bag she only managed to flop over and embed several fallen thorns from the surrounding kiawe trees into her chin. Luckily no one was there to witness it. The large pōhaku sat in a remote valley hidden in plain sight. The beak was carved, but its broad natural depressions strongly resembled the eyes of an owl.

Shark Stones

Ancient stones that resemble sharks are said to have the power to call them from the depths of the ocean. Local fishermen traditionally used the stones to summon sharks to chase fish into their nets in times of famine.

You will still sometimes find stones shaped like fish on lava rock altars throughout the Hawaii islands. Traditional fishermen typically place the first two fish of their catch on the on these fishing shrines for their ʻaumakua, one for their male ancestral guardians and one for their female ancestral guardians.

Sacred Stones Still Persist Today

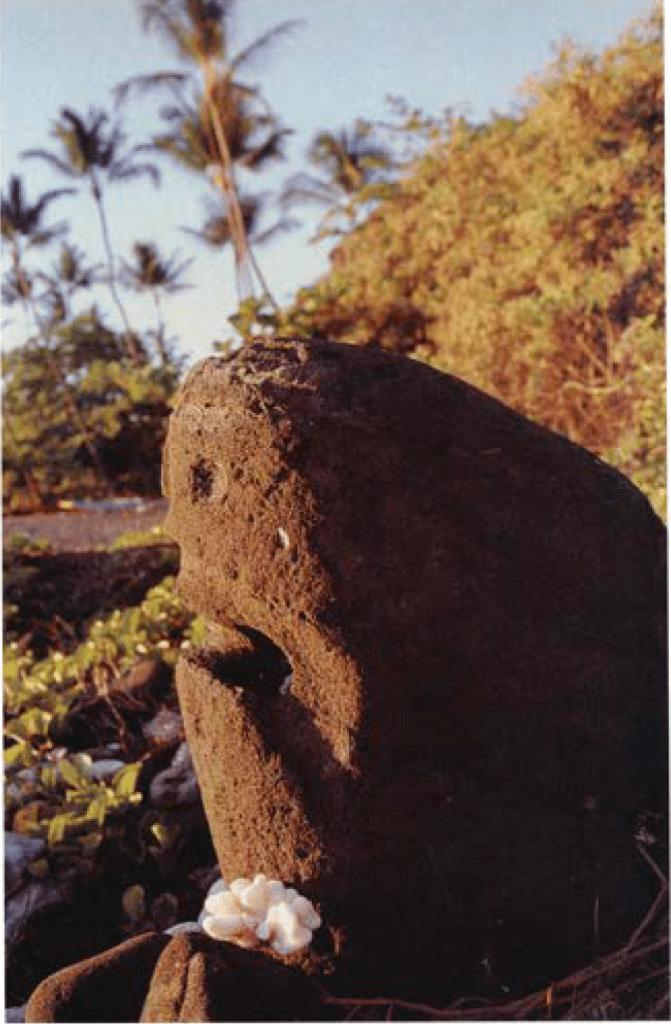

I’ve encountered many pōhaku of note in my travels. One at the Bishop Museum has a similar story to many of the sacred stones Lahe wrote about. His name is Kāneikokala.

Kāneikokala, like many pōhaku, was found by a native Hawaiian driven by dreams. One night in Kawaihae in the mid-1800s an old fisherman named Wahinenui awakened his family to help him rescue a pōhaku who had been pleading to be taken up from a cold, dark place. The family dutifully followed Wahinenui to a spot in the neighbor’s yard where they begin to dig. Below the water table the searchers finally locate Kāneikokala, a stone representation of a shark guardian revered by fishermen.

Wahinenui took in Kāneikokala and treated him like member of the family. Just as the family members are given food, Kāneikokala received regular offerings. Although Wahinenui soon passed away, the family continued to take care of Kāneikokala until they too grew old.

In 1906, James Poʻai, once a young family member of Wahinenui, now an elder, travelled from the Big Island to Oahu. Somehow he had managed to bring Kāneikokala, who is made of solid basalt and ways hundreds of pounds, all the way to the front steps of the Bishop Museum for safekeeping.

Kāneikokala has been a popular addition to the museum collection ever since. He’s a favorite photo opp for elementary school groups and other visitors. Some of the faithful even bring him offerings.

In 2006, upper management decided to remove Kāneikokala and relocate him outside. During the museum redesign that year, although many unsuccessful attempts were made by skilled workers with state of the art equipment, Kāneikokala would not budge.

Staff eventually brought in a kahuna to assess the situation. He informed them that Kāneikokala enjoys being the center of attention and prefers to stay right where he is. Thereafter, all plans to relocate Kāneikokala on the grounds were abandoned.

Some Pōhaku Teach Surprising Lessons

Pōhaku are curious. I’ve certainly encountered some enigmatic sacred stones in the past. There are some I still don’t grasp the meaning of like the deliberately placed black and white standing stones I came upon in 2015 during a hike on Oahu near a cave sacred to a shark ʻaumakua.

Entering this area left an impression an me that I had crossed into another dimension. I felt the presence of spirits perhaps. Although I didn’t understand the message being convened to me at all, I had a strong conviction that something was speaking to me. This was particularly the case when I left this area quickly so as not to show any disrespect.

I took a trail with high grass on either side. I paused when I heard some rustling in the tall grass beside me. A perfectly white pudgy little puppy spilled out and crossed my path, disappearing just as quickly back into the tall grass on the other side of the trail. Right after it, another bounding puppy followed. This one was a carbon copy of the first. The same in every respect, except it was perfectly black.

The fact that the colors of the puppies matched the stones didn’t escape my notice. It did seem like a message. But, if so, I still don’t know what it was, but it wasn’t at all frightening. On the contrary, it was surprisingly heart-warming and made me feel as if the world was safe and incredibly wondrous.

This year (2024) I returned to Oahu to visit family.

2. Lahe Gay made Hawaiian spirituality more accessible.

From a young age, Lahe was immersed in spiritual teachings and practices of Hawaiian tradition. At just four years old, her Hawaiian aunties began training her in spiritual matters. She would go on to and share this insider knowledge in her writing and photography.

The Vision That Saved Her Life

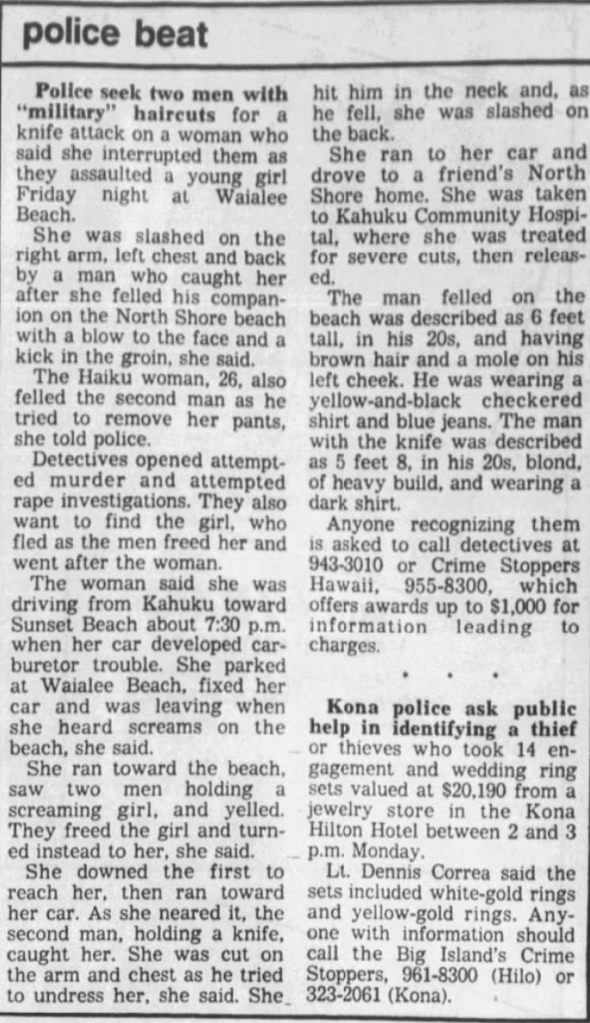

One of the most dramatic demonstrations of Lahe’s connection to the spirit world manifested during a life-threatening situation. When Lahe heard a young girl calling for help on Waialee Beach, she intervened allowing the girl to escape. However, the two would-be rapists, turned on her next.

Suddenly, she saw a figure rise from the sea – the apparition of an ancient Hawaiian. In an instant, this spiritual entity imbued her with the strength to fight off her attackers. She quickly dispatched the first man with a powerful punch in the face and kick to the groin. However, the second man had a knife and slashed Lahe brutally before receiving the same treatment. She got away, but her assailants were never apprehended. This experience deepened Lahe’s commitment to exploring and documenting the spiritual side of Hawaiian life.

Lahe’s unique position as a part-Hawaiian researcher and the last in a line of traditional knowledge keepers allowed her to preserve and then communicate native knowledge to a Westernized audience. Uncommon access to this Hawaiian elders enabled her to combine grassroots expertise with academic archaeological sources, creating a more complete picture of Hawaii’s sacred sites.

Early descriptions and maps of sacred sites from the work of archaeologists John Stokes, Thomas Thrum, and Dr. Kenneth Emory, along with hints provided by elders, aided Lahe in locating pōhaku. However, Lahe’s approach went beyond mere academic study, incorporating oral histories which had been carefully guarded for generations.

3. Lahe Gay devoted her life to the preservation of native wisdom.

Lahe’s work provided invaluable insights into the spiritual significance of pōhaku in Hawaiian culture. She explored concepts such as:

- Mana: The life force or spiritual energy is believed to concentrate at sacred sites.

- Connection with the land: Hawaiian priests gained insights and guidance from meditating in such hallowed places.

- Sacred sites as “transmitters” to the gods: Certain places, or the stones existing at these places, may open a channel for direct communication between mortals and the divine.

Read More . . .

- Guardians of Stone1, April 20, 1992

- Guardians of Stone 2, April 20, 1992

- Rock of Ages 1, April 24, 1992

- Rock of Ages 2, April 24, 1992

- The Future of Hawaii is Set in Stone, April 27, 1992